Reclaiming Design

@ Eames Office

In my previous article I called out that design executives are hired with the same assumptions about their role as those of their peers, that is they are expected to lead a practice area and be an expert practitioner in the discipline.

All to often however, design leaders in an effort to find common ground with their fellow executives over-index on discussing things like analytics, finance, and technology. While this focus on business discourse helps position them as a “corporate leader”, their disinclination to discuss their practice area on par with marketing, sales, and engineering, inadvertently diminishes design. In effect, they are removing design from the conversation.

Old school

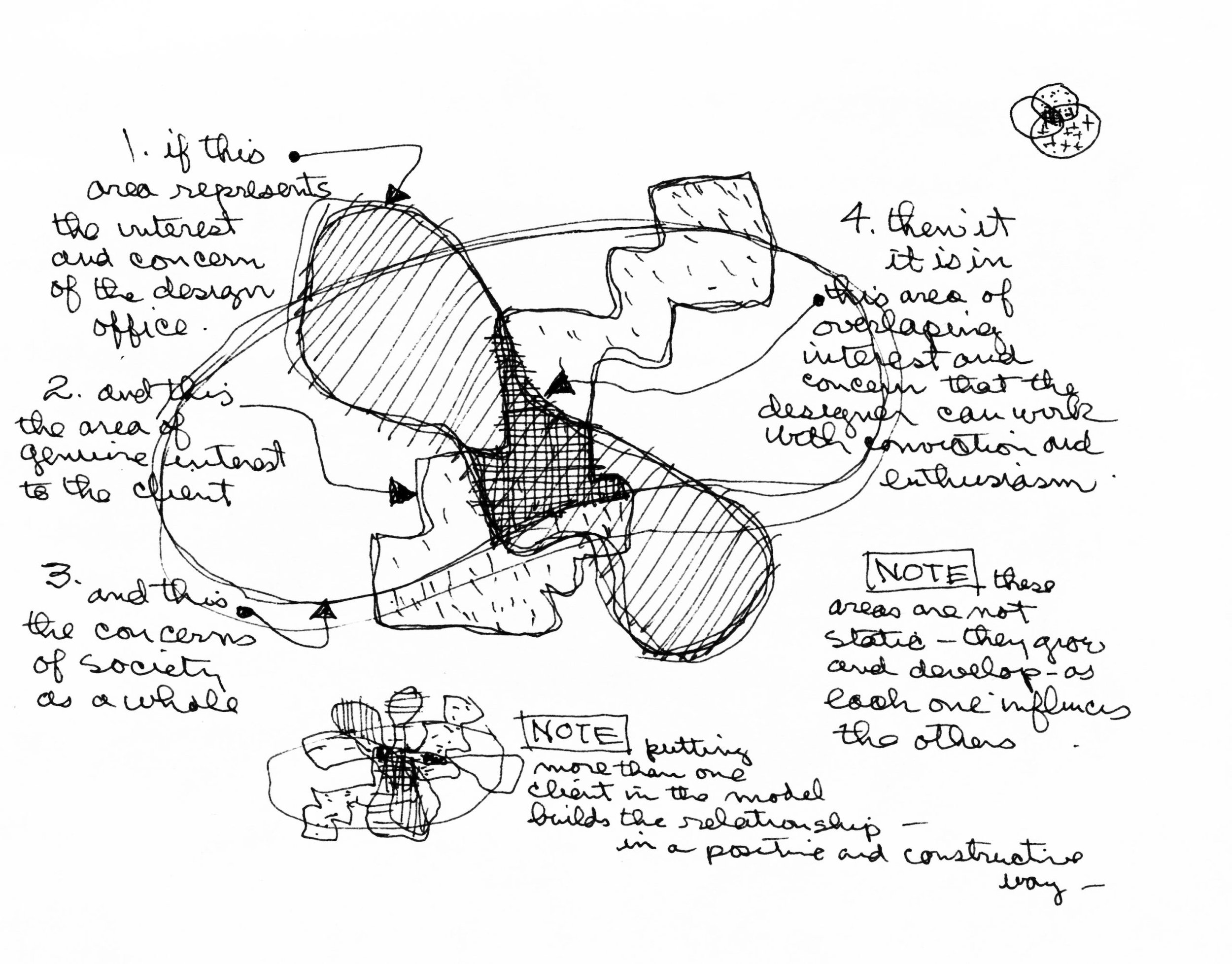

Historically, before the inception of interaction design or user experience, industrial and graphic designers relied on their talent, creativity and expressiveness to deliver compelling designs and impact business outcomes. They would extensively explore new materials, processes, and techniques with curiosity, seeking out novel ways to apply their discoveries to making new products or expand their company’s business into new markets. They relied on analogical reasoning to find novel relationships between different circumstances and plausibility to set their direction. More importantly they talked about design with the assumption that people understood why design matters.

As devices transitioned from mechanical to digital, and human factors expanded from anthropometrics to include cognitive science. Designers began to realized the importance of research and analytics in making products that are not only useful and desirable but also usable, understandable and failsafe. This era gave rise to participatory design and field studies so designers could better understand people’s needs and context. But it was still the designers’ ability to transform those observations into inspiration that drove the creative process.

With the rise of personal computers, design split. There were still the industrial designers creating the enclosures and the physical objects themselves. But now there were also interaction designers who were responsible for designing the digital interface, its metaphors and behaviors, to enable people with not computer science training to use the software in order to achieve their objectives.

From its inception, interaction design was cross disciplinary; comprised of graphic designers (originally trained in print, typography, photography, etc.), psychologists, sociologists, and anthropologists, along with computer scientists and software engineers. This cross functional collaboration resulted in the creation of paradigms we still use today; desktops, folders, files, applications, menus, buttons, icons, etc. This collaboration also introduced designers to the idea of applying the scientific method to research and test their designs. The fact that we still rely on these earliest metaphors, even with with advent of smart phones, VR, and now generative AI, gives testament to the success of this partnership.

Over indexing on the Analytical

Today the world has moved “on-line” with the internet, social networks, and handheld devices. Having a deep understanding of psychology, human perception, problem solving, etc., was critical for designers to ensure people could successfully use one device, or one piece of software (the browser), to accomplish a range of objectives.

By the end of the 20th century, the sciences that once collaborated with designers, had surpassed them to become the primary means of creating innovations, as well as evaluating their value. Many design leaders—myself included, came to rely on analytically driven processes to define requirements, validate designs, prioritize refinements, and explain the value of the design. By extension we also used those analytics justify additional investments in design, user research, etc.

This analytic approach silently pushed design leaders to focus more and more on reliably, that is producing consistent outcomes backed up with facts to prove their worth, add to pursue higher degrees of efficiency within their teams and in the design of their organization’s products and services.

First, we did that by codifying design into a set of guidelines and best practices. Second, we accommodated the request that design should fit into engineering’s agile development model—initially with design happening in real time along side development, later we moved design ahead of engineering by one or two sprints. But design was confined by the two week sprint cycle. And never doubting their engineers ability to improve things, Google reduced that to a single week with thier Design Sprint. At the same time design research was replaced with A/B testing because efficiency. Later and again in response to engineering’s demands, design began the process of codifying design systems; adding symbolic representations of choice to the developer tools, giving companies a standard set of reusable, production ready code snippets to ensure a consistent product every time. Fundamentally a bento boxed lunch complete with the false choice that comes with ordering a personalized lunch.

Unfortunately, in its effort to fit in, design has devolved. Transforming into little more than a collaging exercise—whether its post-it notes on the conference room windows, or making assemblages from design systems that are little more than a box of color forms. While allowing anyone who can sort and arrange prefabricated elements on a screen to now call themselves a designer, the detrimental effect on design’s foundation is reaching irreversible proportions.

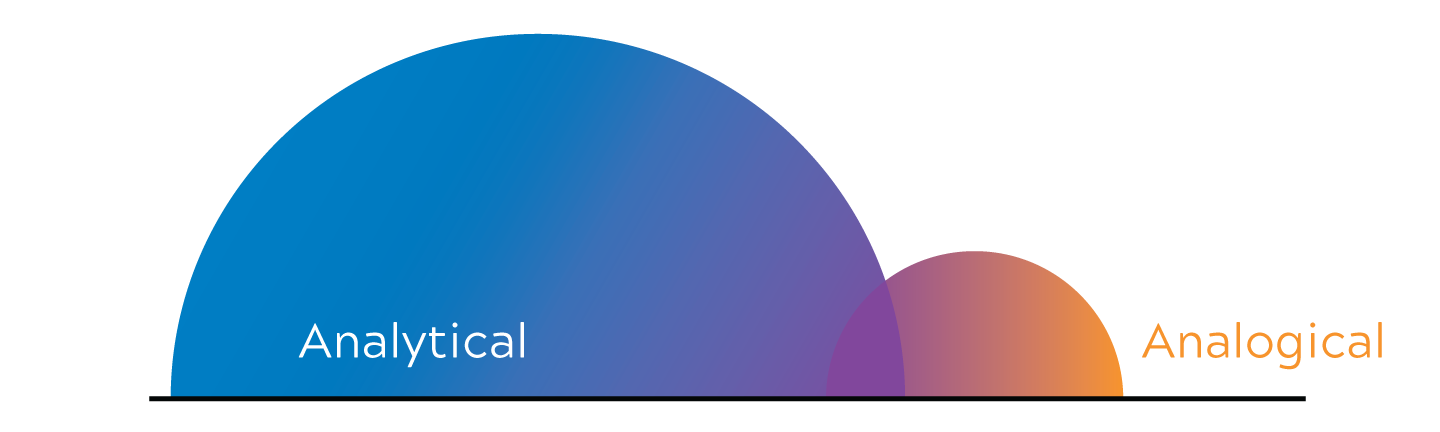

While this begun to increase the reliability of design—getting consistent, replicable results, with fewer variables and requiring less individual judgement and reducing risk; it also came with a very steep price; the validity of the designs—getting the best answer for the given objective by leveraging personal judgement (taste), skills, and creativity.

This analytical approach proven to be extremely reductive; resulting in designs that are repetitive, mundane, and devoid of any significance. There is a palpable lack passion, expression, or anything resembling real creativity. Frankly, it easy to see why some are assuming that generative AI (more likely a simple rules engine, given codification with most design systems) can now do the job a designer.

Looking forward

Once upon a time, design created the future. Today design is about reducing risk.

I am not saying design executives should walk away from their business skills and analytics, but I believe design leaders need to go beyond reliability, and to fulfill their roles as designers: to lead their team in the creation of new things, new paradigms, new languages for interacting with the emerging technologies. To once again create the future. And yes that means taking risks. In short they need to be both analytical and analogical.

Is what I am saying paradoxical? Yes.

But are designers masters of keeping multiple opposing ideas in their heads at the same time? Yes, again.

As we develop the next generation of design leaders, I hope we can help them find the confidence—and indeed the pride, to again talk about design as a first class citizen. We need design leaders who understands that while reliability is important, it still necessary to push the boundaries, to experiment, to take risks and challenge the status quo as well as the data. To do that, design needs leaders who don’t just believe in design, but for whom the act of designing is a core part of who they are.

I am calling on every design leader to step-up and lead design, not manage a collection of resources on a spreadsheet, or evangelize their team’s contribution. To stop apologizing for our processes. And to really lead the design within their organizations, demonstrate what design delivers, discuss its value, obsess over the details. To use design to tell the story of what should be, exploring the semantics and the emotions. And to create designs that break the mold in wonderful, delightful ways.

Are you that leader?