Processes Are Not Real

Regardless if you think the design process is a pair of double diamonds or a set of hexagons and loops, or you think of it as a sprint, an odyssey, or an infinite loop, there is something you need to know about processes: they are not real.

It’s true. And not only are they not real they were never meant to be real. And its not design processes, but all processes.

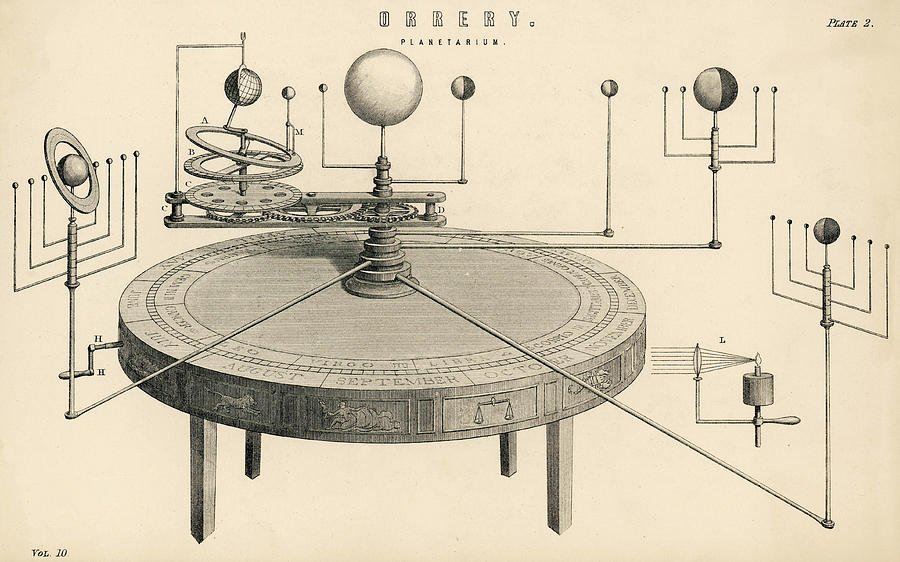

Orreries attempted to explain our solar system. Seeing the world from a god’s eye view was empowering even intoxicating in 1731, but these clockworks solar systems don’t really capture the experience being in the middle of things do they? While they may display the basic mechanics of our orbit, and the orbits of the other planets, they lack the details needed to fully understand the causes and effects. They show none of the physics, they don’t address gravity or momentum, they don’t account for comets or meteorites, and most importantly they don’t capture the actual scale of the experience when you are in the middle of the void—they don’t even mention that there is a void.

And so it is with any process. Attempting to capture a set of complex movements sequenced over time—especially human activities with all our frailties, foibles, inconsistencies and every changing mindset, toolset and skillset, at best a process is a guess at how things may actually play out when we are standing in the middle of the void.

Processes work best when when we remember they are not maps or recipes, they really allegories or parables; they are the stories we share with others to help them learn who we are and what we value. Like the earliest pictographs these processes give us the means to cross the spoken language barriers, and to encapsulate who we are and our activities into a static, two dimensional visualization.

Good processes also embody the shared beliefs of their creators, enabling the rituals they practice to seek inspiration when facing new challenges and solace in times of uncertainty. These artifacts are among the most important legacies passed along to the next generation, helping to ensure continuity in the continuum of cultural development. The orreries provided the means to share knowledge, but more importantly to provoke deeper questions, which in turn expanded the collective understanding of what was actually happening beyond the abilities of a brass clockwork to express eventually leading to the orrery becoming another dustable. Processes need to do the same; provoke the next generation to build on them, to expand them and to eventually replace them as our understandings evolve.

Is it time for design processes to find their spot on the shelf? Not at all, they are still the best means we have for telling our story, for sharing our values and expressing how we can add the greatest value. They are the story of our tribe, and our on-going quest to design.